Madison, Wisconsin, is Mound City.

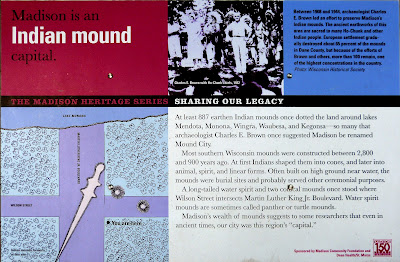

F. Hudson drew this picture of the mound in 1842 when MLK Blvd was called Wisconsin Avenue and Lake Monona was called Third Lake. Increase A. Lapham published it in his 1855 book, Antiquities of Wisconsin.Madison is an Indian mound capitalAt least 887 earthen Indian mounds once dotted the land around lakes Mendota, Monona, Wingra, Waubesa, and Kegonsa—so many that archaeologist Charles E. Brown once suggested Madison be renamed Mound City.

Most southern Wisconsin mounds were constructed between 2,800 and 900 years ago. At first Indians shaped them into cones, and later into animal, spirit, and linear forms. Often built on high ground near water, the mounds were burial sites and probably served other ceremonial purposes.

A long-tailed water spirit and two conical mounds once stood where Wilson Street intersects Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard. Water spirit mounds are sometimes called panther or turtle mounds.

Madison’s wealth of mounds suggests to some researchers that even in ancient times, our city was this region’s “capital.”

Between 1908 and 1944, archaeologist Charles E. Brown led an effort to preserve Madison’s Indian mounds. The ancient earthworks of this area are sacred to many Ho-Chunk and other Indian people. European settlement gradually destroyed about 65 percent of the mounds in Dane County, but because of the efforts of Brown and others, more than 100 remain, one of the highest concentrations in the country.

Erected 2006 by City of Madison.

Lapham says:

A figure on the third lake, within the limits of the town, was fortunately rescued from oblivion by Mr. F. Hudson, whose very accurate drawing I was permitted to copy from the papers belonging to the Wisconsin State Historical Society. It will be seen that it differs from any mound heretofore described, in having a neck and proportionately smaller body. Like most mounds of this general character, it has its head directed towards the water. It occupies high ground, having a gentle slope towards the lake, and is very near the steep broken cliff.William J. Park described the mound as a lizard in his 1877 history of Madison. "Near Lake Monona, adjoining Ex-Governor Fairchild's residence, was a lizard 318 feet long. The figure was rude, but not more than was inevitable, considering that the mound was formed of surface soil, nobody knows how many centuries ago. It was removed in grading Wilson Street and Wisconsin Avenue."

These effigy mounds were built by woodland Indians about a millennium ago. Effigy mound building bloomed in the four lakes area between 650 and 1200 AD. Southern Wisconsin and especially the Madison area was the center of this phenomenon. Although they often contain human remains they are not believed to be primarily burial mounds. They are thought to have marked gathering places for ceremonial purposes. Although mound construction ended around 1200, they continued to be used by the Ho Chunk (Winnebago) as meeting and camping places into the 19th century.

Surviving mounds can be found scattered all over Mad City. Another lizard (or turtle or panther) can be found in Hudson Park at the corner of Lakeland and Hudson Avenues on a bluff above the shore of Lake Mendota.

As this 1921 drawing by Charles Brown shows, the lizard's tail was cut off in the construction of Lakeland Avenue. (from the Landmarks Nomination Form)Lizard Effigy Mound500-1000 A.D.These mounds were constructed by a people of a hunting and gathering culture who met periodically at ceremonial grounds like this one to bury their dead.

The shape of the mound is hard to see on the ground but the lack of close mowing makes the outline a little clearer

and allows wildflowers like this Butterfly Weed to grow on the mound.

Hudson Park is skirted by one of Madison's ubiquitous bicycle paths. A sign warns cyclists not to ride over the Lizard Mound.

The Lizard Mound is the surviving member of a group of mounds called the Mills Woods group that included birds and other figures. The mounds portrayed in grey in this diagram from Birmingham and Rankin have been destroyed by residential development.

Further down Lakeland Avenue in Elmside Park, we find two mounds representing large four-legged animals, identified here as a bear and a lynx, the survivors of the Oakridge mound group.

The Landmark Commission marker has the same wording as on the Lizard Mound marker.

Here in Elmside Park, Ho Chunk artist Harry Whitehorse carved an "Effigy Tree" from an old Hackberry tree that had been struck by lightning in 1991. This snapshot shows the old tree he worked with. (From a collection of photos available here.)

The finished sculpture looked like this:

By 2007, the statue had decayed to the point that arts program administrator Karen Wolf classified it in her "Make Me Cry" category. Woodpecker holes are visible in this snapshot.

Harry Whitehorse took the effigy tree to his studio and re-created it as a bronzed sculpture called "Let the Great Spirits Soar."

Across the isthmus on Lake Menona, there's a bird-shaped mound in Burrows Park with a familiar Landmarks Commission marker.

Each of the bird's long thin wings are 128 feet long. The bird faces Lake Mendota on the west with its tail toward nearby Lake Menona.

Its companion mound, identified as a running fox, was destroyed in 1907. (diagram modified from Birmingham and Rankin)

Great article. I have an article on "mounds" in southern Illinois called the Cahokia complex that may be of interest to you.

ReplyDeletehttp://anamericaninbosnia.blogspot.hr/2013/02/the-cahokia-pyramids-of-illinois-and.html

Thanks Jock!

Delete