The Old Brick Capitol

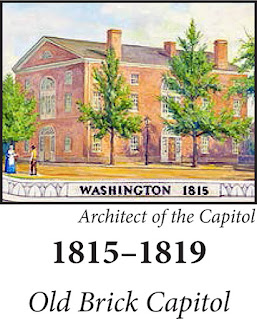

After the Capitol was burned by the British during the War of 1812, the Congress had to meet in more-crowded quarters, using, initially, Blodget's Hotel at E and 8th Streets NW. In 1815, a brick building -- the city's largest privately-built structure -- was erected to better serve the Congress, just to the east of the Capitol across 1st Street, by prominent citizens who feared the capital might be moved away from Washington. For four years the Senate met on the first floor of this building -- in a 15- by 45-foot chamber, and the House of Representatives in a 45- by 75-foot room on the second floor. After the Congress returned to the restored Capitol in 1819, the "Old Brick Capitol" was used by a private school, later converted into a Congressional boarding house, and purchased by the government during the Civil War for use as the "Old Capitol Prison". After the war, private owners drastically remodeled the building into three townhouses, known as "Trumbell's Row". Finally, in 1913, the houses were bought as the headquarters of the National Woman's Party, soon after its organization. The group used the building until 1929 when it moved into the historic Sewell-Belmont House at Constitution and 2nd Street NE. The "Old Brick Capitol" building was destroyed in 1931, after the government had appropriated the site for construction of the Supreme Court Building. (See James Goode's "Capital Losses".) -- DC Hist. Center

This spot had been from 1795 the site of Tunnicliff's City Hotel which by 1815 had become Stelle's Hotel. As Goode tells it:

For a number of years the earlier red brick hostelry, Stelle's Hotel, was managed by Pontius D. Stelle. This Elegantly managed tavern, which faced A Street, was one of the most important in the city's early years, providing not only food, drink and lodging for congressmen and diplomats, but extensive sheds in the rear for the accommodation of coaches arriving daily from Baltimore.

This eighteenth-century building was pulled down in 1815 to clear the site for a temporary meeting place for Congress after the British burned the Capitol on August 24, 1814.

British troops burned the U.S. Capitol when they captured Washington in 1814. Congress met in Blodget's Grand Hotel for one session, during which, private subscribers including Daniel Carroll of Duddington and Thomas Law organized themselves into the “The Capitol Hotel Company”, and built, at a cost of $25,000, this brick structure for the Congress to meet in, on a patch of Carroll's land at First and A streets, then used as a flower-garden, across First Street from the Capitol, next door to Stelle's Hotel, which had to be torn down. The cornerstone of the new building was laid on July 4, 1815. The company charged Congress $1,650 annual rent, which Justice Burton points out was 6% of their original investment.

Congress met in the Old Brick Capitol, as it came to be called, for 4 years. The 14th Congress met at first in Blodget's Hotel in December of 1815 but soon moved to the Brick Capitol. The 15th Congress used the Brick Capitol until March 3, 1819. The Senate meeting on the ground floor and the House on the second floor. Frank W. Hutchins, writing in the Washington Post Magazine Section July 27, 1930, recounts the issues and personalities that dominated the Old Brick Capitol in those years in an article entitled “Shades of the ‘Old Brick Capitol,’” including the exoneration of Andrew Jackson for his unauthorized invasion of Florida and the first consideration of the admission of Missouri to the Union.

But as Justice Burton points out “The most unique incident that had occurred in the Brick Capitol, while Congress occupied it, was connected with the inauguration of President Monroe and Vice President Tompkins, March 4, 1817.” A stand-off in a turf battle between the Senate and Speaker of the House Henry Clay led to President Monroe taking the oath of office outdoors at the Brick Capitol. Burton quotes this excerpt from the debates of the 24th Congress. (“His colloquy of February 28, 1837, is reported in Vol. 13, Pt. 1, of Gales and Seaton's Register of Debates in Congress, 24th Cong., 2d Sess. At 992”)

He {Mr. CLAY [of Kentucky]} remembered that, on the first election of Mr. Monroe, the committee of the Senate applied to him, as Speaker of the House, for the use of the chamber of the House; and he had told them that he would put the chamber in order for the use of the Senate, but the control of it he did not feel authorized to surrender. They wished also to bring in the fine red chairs of the Senate, but he told them it could not be done; the plain democratic chairs of the House were more becoming. The consequence was, that Mr. Monroe, instead of taking the oath within doors, took it outside, in the open air, in front of the Capitol. Mr. C. mentioned this for the purpose of making the inquiry, what was the practice, and on what it was founded, and why the Senate had the exclusive care of administering the oath.

Presidential inaugurations have been held outdoors ever since.

When Congress resumed meeting in the restored Capitol building in 1819, the Circuit Court for the District of Columbia began meeting in the Old Brick Capitol. The Court met in the Old Capitol until 1824. Goode says that “For many years afterward the Old Capitol was used as a private school, and then for many years as a boardinghouse for congressmen. Here, the noted champion of states' rights, Sen. John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, died in his apartment on March 31, 1850, spared from seeing the Civil War he had helped to bring about.”

At the outset of the Civil War in 1861, the government bought the Old Brick Capitol for use as a political prison, housing Confederate sympathizers, spies, opponents of the Lincoln administration etc.

Harper's Weekly, September 14, 1861 had this illustration of “The Political Prison at Washington.”

The prison held many famous, not so famous and infamous prisoners. Including Antonia Ford, Henry Wirz, who was hanged there and various Lincoln assassination conspirators. But the perhaps the most famous inmate was Rose O'Neal Greenhow. Shown below with her daughter in front of one of the boarded-up prison windows.

Elmo Scott Watson insists that the most famous prisoner in the Old Capitol was Belle Boyd.

Leupp in his 1915 book Walks About Washington tell us how Belle Boyd remembered her captivity.

Belle Boyd, who was locked up there for a while, has left us her impressions of the place as “a vast brick building, like all prisons, somber, chilling, and repulsive.” She describes William P. Wood, who was superintendent of the prison, as “having a humane heart beneath a rough exterior.” Every Sunday he used to provide facilities for religious worship to his compulsory guests, announcing the hours and forms in characteristic fashion: “All you who want to hear the word of God preached according to Jeff Davis, go down into the yard; and all of you who want to hear it preached according to Abe Lincoln, go into No. 16.”

The inscription on the back of this war-time photo reads: “Old Capitol Prison for Secesh N or S.”

After the war, in May 1867, the federal government sold the Old Capitol. With financial help from Lyman Trumbull of Illinois , George T. Brown, the sergeant-at-arms of the Senate, bought the property for $20,000. In 1869 Brown had the massive rear wing of the structure demolished, and the main section was remodeled into three large town houses in Second Empire style, with mansard roofs and appropriate Victorian doors and windows. The building was thereafter known as “Trumbull's Row.”

Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper in March of 1880 gives us this look at "The Old Brick Capitol" after its post-war renovation.

But years have cycled into eternity, making war but a memory, peace a reality. The elegant homes of Judge Advocate General Dunn, Judge Field and ex-Governor Lowe form another trinity of human greatness found within the historic walls of this building of checkered career, presenting a delightful contrast between “now and then.”

Lester Hornby drew the Old Capitol in 1915 for Leupp's Walks About The Capital.

Leupp writes that: “At the close of the war the building was divided into a block of dwellings, of which the southernmost was long the home of the late Justice Field of the Supreme Court. The Justice used to enjoy telling his visitors about the distinguished men from the South who, after dining at his table, had roamed over the premises and located their one-time places of confinement.”

In 1921 Trumbull's Row became the headquarters of the National Woman's Party. Elizabeth L. Chittick summed it up in her testimony before Congress in 1974.

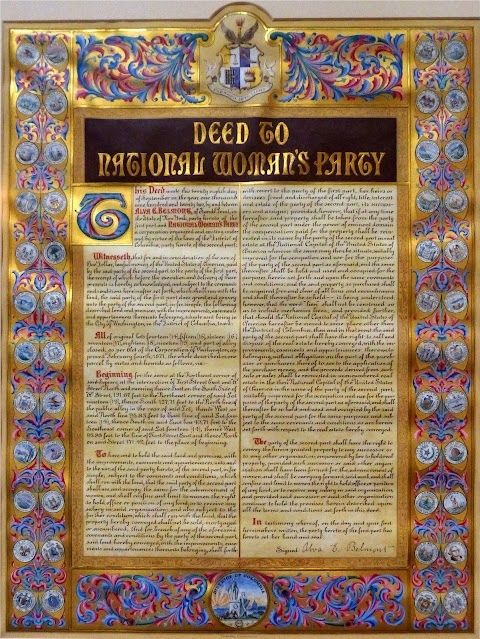

On November 9, 1921, the National Woman's Party bought its first permanent headquarters, the Old Brick Capitol, from Charlotte Anita Whitney, and obtained a mortgage to pay for the property. Mrs. Alva Belmont, a prominent society woman, who had become a strong advocate of equal rights paid off the mortgage on September 30, 1922, and deeded the property to the National Woman's Party, with certain stipulations, some of which are: The property was never to be sold, mortgaged or encumbered; if taken under the power of eminent domain, the compensation paid must be reinvested in another building to be used for headquarters and the furthering of the advancement of women; if the National Capitol of the United States of America be moved to some place other than the District of Columbia, then the party would have the right to sell and dispose of the real estate, and the proceeds reinvested in unencumbered real estate in the National Capitol of the United States of America, wherever that might be.

Alva Belmont's Deed of the property to the National Woman's Party is on display at the Sewell-Belmont House, in which she sells the building(s) to the NWP for $1.

...the said party of the second part shall use and occupy the same for the advancement of women, and shall confine and limit to women the right to hold office or position of any kind, or to receive any salary in said organization...

Here's Alva Belmont (Mrs. Oliver Hazard Perry Belmont), speaking at the dedication ceremony in 1922. (LOC)

Justice Burton ends the story of this site with this summary:

Mrs. Alva Belmont (Mrs. Oliver Hazard Perry Belmont), having acquired the Old Brick Capitol property, presented it to the National Woman's Party as a permanent headquarters for their crusade for equal rights for women. Known as No. 21 First Street, N. E., it was cherished by that organization not only as a head-quarters but as an historical shrine. They embellished the grounds with a garden. When, in 1928, this site was selected for the Supreme Court Building, the National Woman's Party opposed the selection because it meant the removal of their historic building. The Senate adopted a resolution favoring the retention of their building and the abandonment of the proposal to build the Supreme Court Building there. However, Case No. 1911 in the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia resulted in the condemnation of the property and an award to the National Woman's Party of substantially $300,000 as just compensation for the taking of it. Thereupon moved to its present headquarters in the historic mansion on the northwest corner of Constitution Avenue (old B Street and Second Street, N.E.)

As the U.S. Government moved in 1929 to tear down the old buildings to make way for a new Supreme Court Building, a disagreement of the “Ship of Theseus”-type broke out over whether NWP headquarters at 21 First Street was really the same building as the Old Capitol. The NWP certainly believed their headquarters was the Old Capitol. The plaque between the front windows of NWP headquarters in this 1928 photo identifies the building as the Brick Capitol and tells the familiar story.

The plaque pre-dates the NWP at this location. Ellen Spencer Mussey noticed it on the old building and recorded the inscription in her April 1912 article in the American Monthly Magazine, Historic Washington.

The Treasury Dept. concluded that NWP headquarters (Trumbull's Row) was not the historic building that had hosted the Congress after 1814 and had been The Old Capitol Prison. No extra money for historic value was added to the eminent domain compensation given to the NWP by the government. In the photo below Attorney General, Wm. D. Mitchell presents a check to members of the National Woman's Party on March 16, 1929.

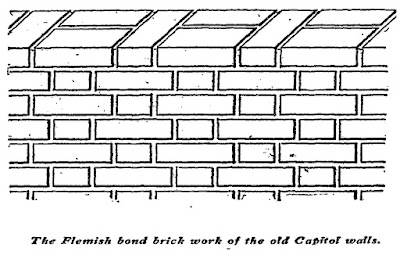

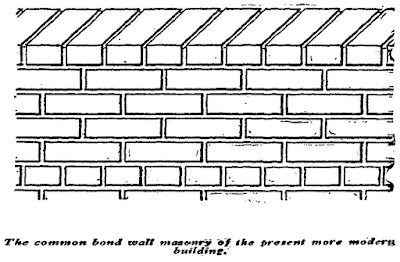

Eyewitness accounts, including Du Puy's report that there was some Flemish bond brick work under the stucco exterior near the foundations. John Clagett Proctor and the Association of Oldest Inhabitants argue that the presence of original structure is enough to justify considering Trumbull's Row to be the same building as the Old Capitol. Ultimately, it's a cultural not a material question. If the Association of Oldest Inhabitants and the National Woman's Party can agree on the historicity of the old building, I have to go along.

The site today is occupied by the Supreme Court of the United States.

No comments:

Post a Comment