Four centuries at the Northeast Corner of Caroline and William Streets, Fredericksburg Virginia

R&R Antiques occupies the Woolworth building where sit-ins took place in 1960, and sits on the site of Weedon's Tavern where, in 1777, Thomas Jefferson, George Mason and others met to launch the Virginia Statute on Religious Freedom. In 1862, Union artillery from nearby Chatham destroyed the Bank of Virginia building on this corner.

Seeking Civil Rights

In the summer of 1960, sit-ins took place around the south. In Fredericksburg, local students staged lunch counter sit-ins in the businesses at the corner of Caroline and Williams Streets. The demonstrations at sit-in corner began here and included W.T. Grant's and Peoples Drug Store as well as Woolworth's:

This enlarged postcard picture of Woolworth's in the 60's is displayed in the antique shop.On July 1, 1960, the protests began when eight students walked into Woolworth’s at 1 p.m. They took their seats silently – some of them reading books – and did not order. Staff quickly put out signs, “This Section Closed.” For an hour the students rotated between the three stores. As soon as the students left, staff reopened the counters to white customers. And so it would go. The Free Lance-Star reported that “Police observed the afternoon demonstrations but indicated they contemplated no arrests unless a trespass complaint was filed by a store.”

An historical marker placed by the City of Fredericksburg tells how the students sought their civil rights in the 1960 sit-ins.

On July 2, 1960, minority citizens of Fredericksburg began a protest to effect social and political change through direct action. A larger Civil Rights Movement had begun in earnest following the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision that struck down as unconstitutional the concept of “separate but equal.” It rapidly spread through much of the South in the form of bus boycotts, freedom riders, and protest marches.

Fredericksburg’s sit-ins occurred at W.T. Grant’s (directly across the street), at F.W. Woolworth’s (across the street to your left front), and at Peoples Service Drug Store (to your right). By late August, the affected businesses relented and integrated their lunch counters.

The local protests were one of many steps taken nation-wide to awaken the conscience of a nation whose creed, espoused in 1776, proclaimed: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal.”

The students in this photo are sitting-in at the Woolworth's lunch counter.

Gaye Todd, the daughter of organizer Gladys Poles Todd was 16 in 1960 when this photo of her picketing on Caroline Street was taken.

MY Stomach May Be Empty But What About YOUR Heart?

Gaye Todd grew up to become Gaye Adegbalola and wrote this account of the demonstrations in 2004.

In 1960, the sit-in movement came to Fredericksburg, VA. I was sixteen years old and full of youthful optimism. We held mass meetings, NAACP Youth Chapter meetings, and mock sit-ins to learn the lessons of passive resistance. When the first day fell, we all had immense fear, but proudly we walked into Woolworth's, Grant's, Newberry's and People's Drug Store. (Remember, there were no McDonalds -- these were the fast food establishments.) We also picketed outside. We made signs nailed to wooden poles. (Remember, there were no magic markers, no quick-print facilities.) (See photo on the bio page.) We sat in for many months -- organized schedules, organized rides. (Remember, few people had cars or phones and there was no public transportation.)Religious Freedom

We were passive and we were polite -- even when called "niggers" and "coons" and "sambo." We were scared when the darkness fell and we exited, surrounded by throngs of whites chanting "come out coons, come out coons!" But we were undaunted and ever so optimistic that our actions would prove to all the world that we were no longer INFERIOR -- as I'd been told during all my formative years. Not by my parents, not by my community, but by life.

By the end of the summer, all stores except for People's desegregated their lunch counters. We'd really hit them in their pocketbooks. Even the theaters, where we had to sit in the balcony and eat the stale popcorn, agreed to desegregate. Yet, as these walls fell, I came to realize that racism ran much deeper than a lunch counter stool.

In 1777, this was the site of Weedon's Tavern, known at the time as Smith's. The tavern was built around 1730 and kept by John Gordon until his death in 1749. This sketch by Philip K. Brown, from Paula S. Felder's book Washington's Fredericksburg shows what it may have looked like -- "based on Assurance Policy No. 6."

George Weedon married Gordon's daughter in 1764 and took over from Gordon's widow, Margaret, as tavern keeper. He had just returned from service under George Washington in the the French and Indian War. In the Revolution, Weedon was second in command to his son-in-law, Hugh Mercer, in the 3rd Virginia Regiment. He became a Brigadier General after the death of Mercer at Princeton in 1777. While Weedon was fighting in New Jersey, a group of Virginia patriots gathered at the tavern on Caroline and Williams streets to discuss revision of Virginia's laws. At this meeting, Thomas Jefferson took on the task of writing the Virginia Statute on Religious Freedom. A Fredericksburg city historical marker across from R&R Antiques marks the location of Weedon's Tavern.

Constructed shortly after Fredericksburg’s founding in 1728, the tavern across the intersection became a popular gathering place under the proprietorship of its first owner, John Gordon, and then of his son-in-law, George Weedon. George Washington was sometimes a guest there.The illustration on the marker is this painting by Cliff Satterthwaite of Thomas Jefferson arriving at the tavern in 1777. (See Felder, Fredericksburg on the Rappahannock River, 2003.)

In January 1777, the Virginia Assembly’s Committee of Law Revisors, met at the tavern. At that time, William Smith rented and operated the establishment, as Colonel Weedon was in New Jersey with General Washington’s Continental Army. Weedon’s son-in-law, Hugh Mercer, was also serving with Washington. Mercer, a doctor in civilian life, had practiced in an office just one block to the north. He died of wounds sustained at the battle of Princeton, while the Committee was meeting in Fredericksburg.

The tavern burned in a fire that swept through these blocks in 1807.

This event was previously commemorated by this monument at Washington and Pitt Streets in Fredericksburg.

The facing plaque explains.

From a meeting in Fredericksburg, January 3-17, 1777, of a Committee of Revisors appointed by the General Assembly of Virginia, composed of Thomas Jefferson, George Mason, Edmund Pendleton, George Wythe and Thomas Ludwell Lee to “settle the plan of operation and to distribute the work” evolved The Statute of Religious Freedom authored by Thomas Jefferson in the document the United States of America made probably its greatest contribution to government recognition of religious freedom.This monument was originally set in front of the Maury School in 1832 but was moved here in 1977. The original plaque, on the back of the monument, displays the Washington worship typical of the 1930's.

This memorial marks the site of a celebration on October 16, 1932, by representatives of the leading religious faiths in America, commemorative of the religious character of George Washington, whose boyhood home was Fredericksburg; and of the separation of church and state, as the Virginia “Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom” was outlined by a committee consisting of Thomas Jefferson, George Mason, Edmund Pendleton, George Wythe and Thomas Ludwell Lee which met in this city on January 13, 1777.The Battle of Fredericksburg

Erected by the State Commission on Conservation and Developement 1932

Weedon's Tavern burned down in the great fire of 1807. In December of 1862, this corner of Caroline and William Streets was occupied by the Bank of Virginia. The Battle of Fredericksburg ravaged the city of Fredericksburg. The red marks on this map by John Hennessy show the buildings that were burned in the battle.

This slightly modified detail shows the Bank of Virginia at the corner of William and Caroline Streets.

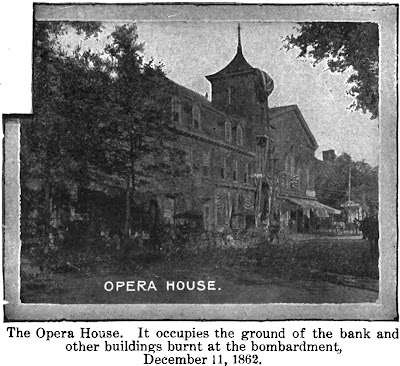

After the Civil War, an opera house was constructed on the site. This photo appears in Sylvania Jackson Quinn's 1908 book The History of the City of Fredericksburg, Virginia:

According to Tony Kent, "In its heyday, the opera house provided a variety of entertainment from Vaudville to Tom Thumb weddings, the John Philip Sousa Band, minstrel shows. William McKinley and Grover Cleveland were welcomed here." The Opera House, built in the 1880's, was torn down in the 1950's to be replaced by the neo-Georgian Woolworth's building. When Woolworth's closed, it was succeeded in 1980 by R&R Antiques.

Make Your Money Last -

Invest in the Past

Some of the history of Fredericksburg can be found in the antiques shop window.

This fallout shelter sign reflects the Cold War heritage of the building.

A graffito face on a neo-Georgian vase peers from the roof of R&R Antiques.

excellent issues altogether, you simply won a brand new reader.

ReplyDeleteWhat could you suggest in regards to your submit that you simply made a few days ago?

Any certain?

Feel free to surf to my website - naildesignsart.org - ,